- Product

- Documentation

- Blogs

- Contact us Exchange

Zero-Sum Games

One notable thing about financial markets is that often - not always, but often - they can be a zero-sum game (where one person’s gain is equivalent to another’s loss). If you buy a share in a company that is not a zero-sum game. The company could create value through its operations which drives the price of the stock up. You can make money without anyone else losing money! Win-win! If you buy a call option, that is a zero-sum game. The amount of money that you gain or lose is necessarily equal to the amount of money someone else has lost or gained by underwriting that option. If you win, they must lose, and vice versa. That is not to say that options or other derivatives are bad and stocks and spot trading are good, but they are simply very different in terms of how the market participants realize value.

The same can be said about different trading strategies. Buying and holding is not a zero-sum game. High-frequency trading and market making are zero-sum games. Again, it’s not that one is better than the other, they are just different and serve different purposes. Market makers are important to the long-term holders (and other traders) by ensuring that markets are liquid enough to allow people to enter and exit positions. In exchange for this service, the other traders accept that there is going to be a spread and that they may be executed at prices which are marginally worse than the theoretical market value of the asset at that precise point in time. Market makers are not benefitting from the long-term value accrual of corporations by means of those companies’ operations. Their goal is to be market-neutral - to neither be long nor short any asset in which they make markets for. This allows them to avoid taking any directional risk. They simply make money from the bid-ask spread, and that’s all they are trying to do.

Maximizing Value (but only for them)

It is no secret that companies try to maximize value for themselves. A lot of the time, there is nothing wrong with that. For example, a company creates new products so they can deliver more value to customers and thereby charge more. Sometimes value maximization comes at the expense of others. For example, a company has a pay cut to improve its profitability. Companies can create value for themselves by creating value for everyone (win-win) or by taking it from someone else (zero sum).

If you live outside the United States, you may not remember the Robinhood / Citadel fiasco of early 2021. Long story short, Robinhood is a stock brokerage which pioneered the free trading model in the United States. It is a nearly universal rule that when something is “free”, you are the product. Think about Facebook or any social media company. Social media platforms are free because you give them their data so they can target you with ads. You are the product that they sell to their advertisers. Robinhood did a similar thing, only the data was users’ order flow. They sold the order flow to Citadel Securities (this is known as payment for order flow, or PFOF), who could decide whether they wanted to fill the order before anyone else could. Robinhood made 80% of its money that way. The SEC fined them $65 million for lying about it and providing customers with worse trade execution, arguing that the trades weren’t “free” at all, the costs were merely obfuscated in this PFOF arrangement. Then Gamestop happened, Robinhood turned off the buy button, and a generation of retail traders woke up to the fact that the institutions who were running their markets are maximizing value, but only for those institutions. It was a zero-sum game slowly being ever more rigged for retail traders to lose.

Few people would argue that it is bad for brokerages like Robinhood to charge fees. That is how they get paid for the service they provide of letting users buy and sell assets. The problem is the way in which they were doing it:

They tell you they have no fees.

They sell your orders to someone else who skims off the top.

Everyone on the platform gets worse execution.

Another important point: for the traders themselves, there is no functional difference between payment for order flow (selling your orders to a third party) or order internalization (the exchange or broker you are placing the order with acting on those orders themselves). The SEC sums this up nicely in a 2000 study on PFOF and order internalization: “Payment for order flow and internalization create conflicts of interest for brokers because of the tension between the firms' interests in maximizing payment for order flow or trading profits generated from internalizing their customers' orders, and their fiduciary obligation to route their customers' orders to the best markets.”

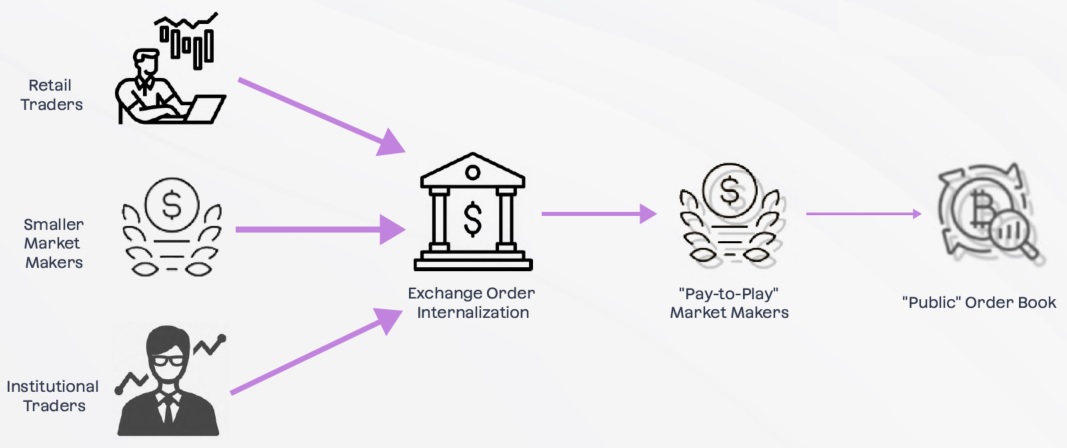

The main problem here is a system of “first dibs” - effectively, the broker / exchange (for example FTX) or its favored pay-to-play counterparties (for example Alameda) get to see and act on the orders before anyone else. They are the beneficiaries of information asymmetry. This creates a market with different rules for different participants, and you, the traders, get the worst set of rules so the institutions can maximize their profits in the zero-sum game. In practice, traders’ orders are filled less often, are filled at worse prices, and are more likely to be filled when the market is moving against them. This is known as “adverse selection”.

This is what happens when exchanges (or brokerages) internalize orders and sell their order flow. The exchange and its favored, pay-to-play counterparties have more information about the order flow and preferential access to the order flow. This allows them to take orders which they can profit from nearly immediately. Their profits come at the expense of both the parties placing the orders and the parties who have orders already on the order book.

If You Put A Dollar In Front Of Someone…

Should you not have guessed, the previous examples of FTX and Alameda were intentional. In the collapse of FTX, it was discovered in a CFTC lawsuit that FTX gave Alameda many special advantages which allowed them to trade more rapidly than all other market participants. A separate CFTC lawsuit against an even larger crypto exchange showed that the exchange and its founder are “the direct or indirect owner of approximately 300 separate [exchange] accounts that have engaged in proprietary trading activity on the [exchange] trading platform.” While the lawsuit does not mention order internalization specifically, it stands to reason that if they are willing to risk legal liability to onboard US institutional traders to increase their profits, they will also increase their profits by internalizing their order flow, as that does not have any risk of legal liability.

The lesson we should learn is that if you put a dollar in front of someone, they will take it. In the case of crypto exchanges, the exchanges and their favored counterparties are taking those dollars from the other market participants and pocketing them, simply hoping that the amount is small enough or their actions obfuscated enough that you don’t notice.

While certain executives of cryptocurrency exchanges have described the practice of trading on their own exchange as “eating their own dog food”, suggesting that it is good they use their own products, exchanges are not dog food. If a dog food executive buys his company’s dog food, there is no possibility for harming or disadvantaging anyone else who is also buying the dog food. If a crypto executive, or the company itself, trades on their own exchange, it is very possible that they are giving themselves an unfair advantage, which does disadvantage other market participants. This is the problem with any trading on one’s own exchange for financial purposes (as opposed to a technical purpose, such as for testing). No one except the exchange themselves knows whether they are giving themselves an unfair advantage. There are dollars in front of them: do you think they are more likely to take those dollars or to leave them?

Remembering Trustlessness

Centralized financial systems are not without their benefits. DeFi has yet to be able to replicate its efficiency, throughput, speed, and cost advantages. The sacrifice they ask us to make in exchange for those advantages is primarily one of trust.

Blockchain and DeFi were built for trustlessness, but centralized systems have yet to be able to replicate it. Until they can, all centralized financial systems will necessarily require trust. Decades, if not centuries, of financial history have demonstrated that those who are capable of exploiting others will eventually do so. The crypto-financial system was invested to escape that previous reality. We must deliver a system which does not require those trade-offs.